|

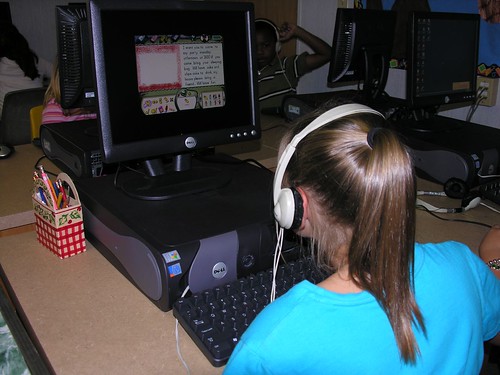

| Photo courtesy Old Shoe Woman via Flickr |

What happens when students fall behind in their reading skills? As adolescents, "students should make the leap from learning to read to reading to learn and should be capable of reading to solve complex and specific problems (Urquhart Engstrom, p.30). For many students in our school systems, a learning disability (LD) makes it difficult for students to make the shift to reading to learn, especially in text-heavy courses.

In Ontario, defined by the Learning Disabilities Association of Ontario, "learning disability"

"...refers to a variety of disorders that affect the acquisition, retention, understanding, organisation or use of verbal and/or non-verbal information. These disorders result from impairments in one or more psychological processes related to learning (a), in combination with otherwise average abilities essential for thinking and reasoning. Learning disabilities are specific not global impairments and as such are distinct from intellectual disabilities."One solution is to design the class to meet the individual needs of those most at risk of not doing well -- that is, students with special needs. Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is defined by the Ministry as a "teaching approach that focuses on using teaching strategies or pedagogical materials designed to meet special needs to enhance learning for all students, regardless of age, skills, or situation". The catchphrase, "necessary for some, good for all" sums up the general idea well.

Common Misconceptions of Learning Disabilities:

The most common misconception is that students with LD have cognitive impairments or limitations; in fact, students with LD are able to function at age appropriate cognitive levels when they are provided appropriate tools to accommodate for their LD. Generally, students with LD have difficulty in oral communication, writing, reading, and mathematics.Another misconception centres on how an individual "attains" an LD; in fact, learning disabilities are biological in nature.

"Learning disabilities are due to genetic, other congenital and/or acquired neuro-biological factors. They are not caused by factors such as cultural or language differences, inadequate or inappropriate instruction, socio-economic status or lack of motivation, although any one of these and other factors may compound the impact of learning disabilities. Frequently learning disabilities co-exist with other conditions, including attentional, behavioural and emotional disorders, sensory impairments or other medical conditions." (Learning Disabilities Association of Ontario)So, since students with LD are cognitively able to do grade or age appropriate work, then what are some of the technological accommodations available to help with literacy? What tech tools can teachers embed into their classes using Universal Design?

Common Tech Tools for use as Assistive Technology in UGDSB:

Education for All (2005) defines assistive technology as "any technology that allows one to increase, maintain, or improve the functional capabilities of an individual with special learning needs (Edyburn, 2000). Its applications and adaptations can help open doors to previously inaccessible learning opportunities for many children with special needs (Judge, 2001)" (p.127). In Ontario, many of these tech tools are provided, at no charge, to students.

Read & Write for Google: This web-based Google application (to be used in Chrome) will read aloud text in multiple formats - Google Docs, the Web, PDFs, ePub, and Kes (Kurzwell 3000 Files). The application sits right over top most pages launched in Chrome and is activated either through a drop down tab & menu or through the extension link in your toolbar. The voice can be customized (multiple choices and accents are provided as it is a global market); students are able to create their own, printable dictionaries (standard and pictorial) and vocabulary lists; a prediction tool helps with spelling; and students can directly search terms that may not be clearly defined in the reading.

Kurzweil is software which promotes independent reading and writing in students with LD by converting scanned text and images into pages that can be read aloud by the computer (students can choose from a number of voices). Files are editable, so that students can also write tests and compose their own writing on computers.

Word Q and Speak Q: these programs suggest words and read aloud words for students while sitting overtop their regular software programs. Especially useful for those with challenges with spelling and auditory processing.

Dragon Naturally Speaking: speech recognition software which allows students to dictate their notes, tests, essays, etc. Students can train the software to recognize their voice and essentially allows students to run their computer programs using their voice, which is significant for those with processing delays or students having difficulty writing.

Promethean & Activ Inspire: Promethean multi-touch, interactive whiteboards and the sophisticated software allows students to actively engage and collaborative in a digital context. Students can interact with the software through their tablets or interactive devices, allowing teachers to collect data and provide immediate feedback to students.

Smart Ideas: SmartBoards and the software, Smart Ideas, allows students to actively engage with a touchable and computer-like, interactive whiteboard screen. The package is engaging, collaborative in nature, and appeals to multiple modalities in students. Smart Clickers also allow teachers to collect data from students and provide immediate feedback.

Smart Ideas: SmartBoards and the software, Smart Ideas, allows students to actively engage with a touchable and computer-like, interactive whiteboard screen. The package is engaging, collaborative in nature, and appeals to multiple modalities in students. Smart Clickers also allow teachers to collect data from students and provide immediate feedback.

Smart Ideas: SmartBoards and the software, Smart Ideas, allows students to actively engage with a touchable and computer-like, interactive whiteboard screen. The package is engaging, collaborative in nature, and appeals to multiple modalities in students. Smart Clickers also allow teachers to collect data from students and provide immediate feedback.

Smart Ideas: SmartBoards and the software, Smart Ideas, allows students to actively engage with a touchable and computer-like, interactive whiteboard screen. The package is engaging, collaborative in nature, and appeals to multiple modalities in students. Smart Clickers also allow teachers to collect data from students and provide immediate feedback.Need help with these programs? Contact your Resource teachers and those with Special Education Specialists. Much of the software is available through the OSAPAC (Ontario Software Acquisition Program Advisory Committee).

Why use these technological supports?

Today's technology allows students with LD to participate like never before; many tools are free to all students in Ontario (through OSAPAC) and require little training. Most importantly,"Two major reviews of the research in assistive technology (MacArthur, Ferretti, Okolo, & Cavalier, 2001; Okolo, Cavalier, Ferretti, & MacArthur, 2000) confirmed the utility of computer-assisted instruction and synthesized speech feedback to improve students’ phonemic awareness and decoding skills, as well as the benefits of electronic texts to enhance comprehension by compensating for reading difficulties. Assistive technologies include text-to-speech software, word-processing programs, voice-recognition software, and software for organizing ideas.While these technologies are relatively new, they hold the promise of bridging the gap between a student’s needs and abilities." (Urquhart Engstrom, p.31).

Integrating explicit instruction of reading strategies and assistive technology can improve content area comprehension. Students can improve accuracy, speed, and comprehension of text which will therefore allow them to better demonstrate their understanding of course material. More importantly, students with LD are cognitively capable of grade-appropriate work and need academic challenge; limiting critical thinking, using low level vocabulary for academic vocabulary, or substituting easier texts for challenging texts should not be accommodations. Rather, teaching students how to access these texts using assistive technology will enable success. To best accommodate our students with learning disabilities, we need to ensure careful planning and classroom instruction which will accommodate for any deficits a student may be experiencing.

References:

Ministry of Education (2005). Education for All: The Report of the Expert Panel on Literacy and Numeracy Instruction for Students With Special Education Needs, Kindergarten to Grade 6 "Computer-based Assistive Technology” Ch. 10, pp. 127-138.

Ministry of Education (2010). Caring and Safe Schools in Ontario: Supporting Students with Special education needs through progressive discipline, Kindergarten to Grade 12.

Urquhart Engstrom, Ellen (2005). "Reading, writing, and assistive technology: An integrated developmental curriculum for college students." Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy 49:1. pp. 30-39.